Releasing trauma and improving brain signals with a PoNS machine

Decoding signals between the brainstem, neocortex, and the body

Many conversations about trauma begin with a crash course in polyvagal theory, which describes the vagus nerve and the body’s fight-flight-freeze mechanism. I was conceptually fascinated by this idea at first, but mystified about how to move the energy through and out of the body. Trauma is as much about our emotions as it is about brain (psych) and nervous (soma) system structure and function. Later, as I underwent brain stimulation therapy, I experienced one of the on/off switches in the prefrontal cortex. With lingering curiosity about that profound experience, I’m now exploring the brainstem, the oldest part of the brain.

The prehistoric nervous system

Our prehistoric nervous system is a single system that winds its way from our brain to our heart, limbs, and digestive system. The system is hardwired to avoid threat and seek reward (topics that happen to align well with anchoring discourses of moral philosophy… hmmm…).

Our senses are attuned to threats and rewards in our immediate environment, and we overreact to negative stimuli when our brains “save” negative experiences. Brains and nervous systems that get messed up aren’t properly (or, you might say, “too properly”) attuned to the environment. Sometimes, we become improperly attuned to our own body-as-threat, leaving the system in a constant frazzled loop.

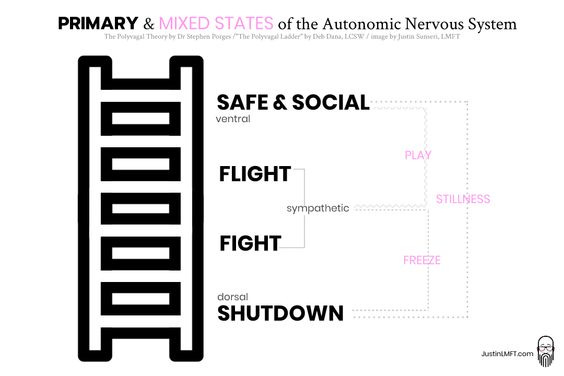

Porges’ polyvagal theory describes a “ladder” for our default nervous system state from (1) freeze at the bottom to (2) fight-flight, and then up to (3) rest-digest mode. Many folks with brain injuries end up stuck at the bottom of the ladder because the body, in all of its infinite and endlessly frustrating wisdom, knows that something is deeply wrong, and then it… Shuts. You. Down.

Polyvagal theory is articulated like this (emphasis added):

Polyvagal theory (developed by Dr. Stephen Porges) identifies three whole-body states our nervous system continually moves between, depending on activation of the vagus nerve:

Ventral vagal—a state of being socially receptive, calm, productive, and feeling safe in the world around us and in our own being. [“rest and digest”]

Sympathetic—the famous fight-flight response kicked off by the detection of threat, whether it is real or imagined; we respond by either going into rigid defense or getting out of Dodge.

Dorsal vagal—the most intense response to threat, when it is overwhelming—total and complete shutdown, often against our will. We struggle to function at all; we often feel shame as a result of this mode, and experience sensations of numbness, dissociation, and overwhelm.

And this may be the most important point: Your vagus nerve will react whether you like it or not (!) because the safety system of the human body rests on one motto: Better safe than sorry.

Soon after withdrawing from the sleeping drug, I realized that this problem was in my body and not just the “mind,” as we typically understand it. Talk therapy and cognitive reframing exercises weren’t making any progress. If anything, they sometimes seemed to make things worse, but I didn’t know quite why. I just knew my “effort” wasn’t paying off. Something was stuck in my body and had to get “unstuck.”

I retained my metacognition, which is the awareness of what I’m thinking and why, even if my perception was out-of-whack. I was not hallucinating and I was not delusional. I was in pain, I was an embarrassed and isolated wreck, and I couldn’t just cognitively re-frame my experience to get better.

Somatic therapy

I finally began to get a sense of how this mess was stored in my body after chatting with a Dutch expert on chemical-induced brain injuries, who recommended I try somatic therapy.

On a desperate video call in the fall of 2021, after about 6 months of failed experiments with pharmaceuticals and idiot professionals, the Dutch expert said that it was as if my precognitive “limbic” system was continually signalling that I had been attacked by a tiger, and that I could be attacked again at any moment. In response, my body put me into “turtle mode.” Complete overwhelm, with no help on the horizon.

That didn’t seem to explain the loud tinnitus, brightness of certain lights, problems with visual pattern recognition, or weird sensations in new spaces, but then again he had witnessed several folks who were afflicted by something similar, so he had some good data to work with. Hypothetically, any animal would want to stay put if its visual and auditory signals were overactive (what does it look like from within a turtle shell, anyway?). To add one more animal metaphor into the mix, he said I should try “shaking like a deer that was attacked by a beast.”

Soon after that call, I began working with a determined and wise somatic therapist, who witnessed many folks get stuck in freeze mode during the pandemic. She also recognized that co-regulation with other nervous systems was a key piece of the puzzle. In other words, the isolation wasn’t helping.

She is an excellent teacher in all things vagus. Through breathwork, movement exercises, and connections to people who would help with coregulation, we unpacked layers to the trauma—the brain injury as well as the complex feeling of isolation that comes with it, not to mention the life circumstances leading to the mess. Many folks also work on body-stored trauma by doing yoga, tai chi, or qi gong, and star experts like Drs. Peter Levine and Gabor Maté validate the approach. I’ve recently started qi gong, too.

Somatic therapy provided some relief, but in spite of my effort, I kept falling back into freeze mode until magnetic therapy (rTMS) on my prefrontal cortex (PFC). rTMS was a stepping stone to spending time in Switzerland, which was another physiological boot camp (in fact, travelling is one of the best ways to induce neuroplasticity).

With the greatest success following electrical stimulation therapy, I’m now giving the PoNS machine a try. It stimulates the brain through a different channel.

The brain-body interface: the brainstem and periaqueductal gray

The brainstem is the interface between the body and the brain. It modulates signals that come up from the body, which are then decoded by the brain, and sent back out to the body. Emotions are one of the complex “languages” human bodies have to understand how to direct energy throughout the brain-body system to maximize reward and reduce threat.

The PoNS machine, which costs about as much as a small car, sends electrical signals up the tongue to the brainstem. The device turns on sensory neurons through the cranial nerves to the brainstem, and then on to whole functional brain networks, depending on which ones are being activated. The machine itself doesn’t stimulate the whole brain, but it jumpstarts an electrical cascade in the brainstem and sends it on to the rest of the brain. Most brain functions take place in widely distributed networks, not centralized areas. These networks are “functional systems” that affect many brain areas at once.

In The Brain’s Way of Healing, Dr. Doidge describes how PoNS-induced electrical signals enhance neuroplasticity and either restore or reset some of the brain’s interneurons. The effect reduces “noise” or sensations of overstimulation by regulating signals that fire between primary neurons. A functioning sensorimotor system requires constant feedback between the body and brain, and that critical feedback can become unsynchronized, disrupted, or too low.

Exercising while using the PoNS also seems to increase synapse and receptor size, which further improves the signal along the nerve axon. I have yet to take advantage of this benefit, because I guess there’s part of me that doesn’t know how to embrace walking around in public with a machine in my mouth.

The PoNS is usually prescribed to folks with MS, Parkinson’s, or traumatic brain injuries (TBI), because folks with these problems frequently have impairments to balance, movement, sleep, thinking, and/or mood, even though the damage affects different parts of the brain. For those with mobility issues, a short stint with the PoNS device can enable them to miraculously walk again. With repeated use (20 minutes a day 5-7 times a day), the device can help folks recover everything from balance to vision to sleep. For me, this device has had a hugely positive impact on my sleep-wake rhythm.

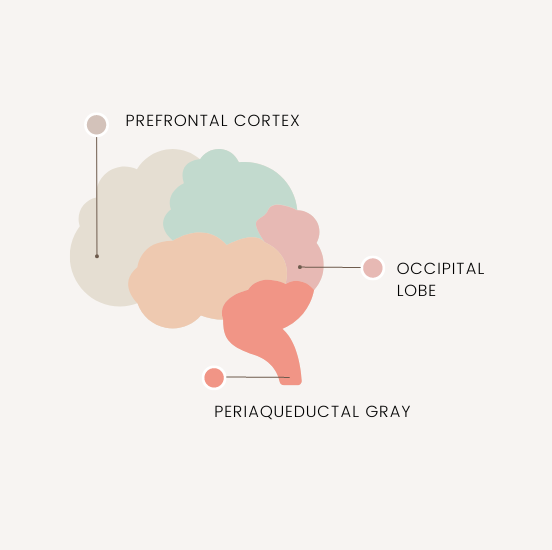

For folks with injuries like mine, it’s possible that the device sends signals through the periaqueductal gray, near the vagus nerve’s origination point. This part of the brain helps to modulate autonomic function, motivation, breathing, sleep, and the dreaded "freeze" mode.

As I mentioned before, rTMS taught me a lot about the prefrontal cortex (PFC)—the front part of the brain and our most recently-evolved brain structure. A lot of research focuses on the role that the prefrontal cortex, amygdala, and insula play in harnessing our willpower, attention, and emotions. Often described as our “executive” cortex, the prefrontal cortex gatekeeps many of our base or “primal” functions like breathing, motivation, and responses to threat stimuli. The amygdala and insula modulate our fear and subjective emotional responses, respectively.

But the periaqueductal gray (PAG) is the part of the brain that originates the signal, sending it up from the body, through the brain’s chain of circuits, and toward the PFC gatekeeper (and then back again). This region of the brainstem is part of our “oldest” part of the brain, playing a central role in autonomic function, including breathing, primal motivations like sex or hunger, and responses to threat stimuli (“aversive behaviour”). It’s one of the most important centres for pain modulation, and it’s now being studied for its role in behaviour changes in post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

It seems to me that the PAG and brainstem are the perfect place to target in my rehabilitation effort for the moment. I can’t overstate what a relief it’s been to experience a more normalized sleep-wake rhythm. I’m finding myself more rested, relaxed, and curious, in some semblance of my former self. If I use the machine while I read, write, or drive, I can focus and feel my sympathetic vagus nerve release. My neck relaxes on the right side, and I have more sensation on the left side of my body. My breathing normalizes.

I am not counting my chickens yet, though. I went to a professional soccer game last week, and the experience of being in a stadium with all the sounds, colours, movement, and light, was unreasonably exhausting. I was not heartened by that experience. Some folks only see major results after using the PoNS device for weeks, months, or years. So time will tell.

And while the PoNS hopefully works its magic, in the meantime, I’m getting trigger-point injections for the ungodly stiffness that has plagued the right side of my body since the injury. I’ve only had one injection so far but the effects have been miraculous—like a massage that lasts for weeks.

So there’s some good news here, but I’ve got to be patient with these therapies before I really start celebrating. Nevertheless, I’ll take what I can get for now!