Firing electrons at the brain to revive willpower and attention

I lost these two of my superpowers after nearly two years of intense pain

I wouldn’t be in Switzerland, I wouldn’t be able to sit and write, and I might not even be alive, if it wasn’t for two things: ongoing daily encouragement from close friends, and my recent rTMS treatment (ie. repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation). It dramatically improved my willpower and attention — two things I used to have in spades. Indeed, my initiative, willpower, and attention had carried me through life and were critical for the kinds of jobs I had, including research and teaching, or being a musician and entrepreneur. rTMS even improved my appetite, which I had lost for awhile.

In some chronic pain disorders, including fibromyalgia and major depression, the left side of the prefrontal cortex (the “dorsolateral prefrontal cortex” or DLPFC) can become dormant.

[Just a warning: it gets a little technical in this post. Forgive the jargon.]

This is the “dark side” of neuroplasticity — brains have this incredible ability to heal, which I’m reminded of again and again — but it’s also clear that they can get in their own way and get stuck. Then they need a nudge to get out of the loop.

I was inspired to learn more about this phenomenon after reading The Ghost in My Brain: How a Concussion Stole My Life and How the New Science of Brain Plasticity Helped Me Get it Back, by Dr. Clark Elliot. He is also a professor and musician who suffered a perceptual hell after a traumatic brain injury. He found a path to healing after an incredible 14 years, during which time his brain misdirected all kinds of signals. He recovered after seeking treatment at Chicago’s Mind-Eye Institute, and that inspired me — both the length of time it took for him to find a solution and the fact that he actually found one. I needed my own series of nudges to get out of the loop. I’d start with rTMS and then set up a consultation with Mind-Eye before heading to Switzerland to explore other possibilities. This had, for now, become my life purpose.

So as I discovered, when the body’s pain signals are overwhelming, the part of the brain tasked with noticing these signals (and then finding solutions to them), can shut down. It tries to help by reducing awareness.

A malfunctioning DLPFC is associated with other problems: the “inability to detect errors, difficulty with resolving stimulus conflict, emotional instability, inattention,” and more besides. Sounds like fun, right!?

One of the reasons for emotionality with a dormant DLPFC is that we can’t use attention and will to “reframe” a particular situation. This is something that just about anyone who is either neurotypical or has not experienced a brain injury has a lot of trouble understanding. The brain’s protective process is a major obstacle in the ability to function, take responsibility, and ideally, turn a life around.

How the treatment works

rTMS on the DLPFC seems to help with a variety of neuropsychiatric disorders that affect the central nervous system, including major depressive disorder, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) — which just about every therapist I’d worked with had decided I was also plagued with. There are different frequencies and target areas for rTMS, but the treatment I received is the most popular and best-researched.

Not only does rTMS use a variety of frequencies to “wake up” (or, if desired, shut down) the DLPFC, but excitatory treatment has positive cascade effects by reducing activity in the amygdala, insula, and anterior cingulate cortex (ACC). The amygdala governs some of our fear responses, the insula governs some of our pain perceptions, and the ACC also helps regulate mood and attention.

As you can imagine, it seems to be a pretty promising treatment for someone stuck in an overwhelming sensory-driven pain loop. I was also lucky to have weaned off of anti-epileptic medications that would have been prohibitive for the treatment (I’ll explain those another day).

In my case, we used a theta-burst electrical frequency (iTBS), which generally has the advantage of being short in duration (about 10 minutes per session) but fast-acting and sustained over time (months, if not years). Here’s a summary of research about the efficacy.

Like a robot under remote control

The treatment was suggested by a good friend of mine who knew that I was at the end of my rope. She’d been in touch with a range of practitioners, and this was something I had not tried. It was expensive, and, once again, wasn't covered by government health insurance, but I decided that the only way to climb back to life would be to try these expensive therapies. The government medical system had nothing to offer.

After a caring and fruitful assessment with the doctor, I was seated in the treatment chair and they measured my head. The targeting system guesses at the likeliest place to hit based on the size of your noggin. It synthesizes a picture of your brain based on a composite of MRI scans from many different human brains.

Then they started firing, first at the motor cortex, to secure an accurate target. For this test round, they were going to make my hand move.

Zap. My finger moved a bit on my right hand. They shifted the magnet over slightly and fired again. My finger moved more. I felt like a robot under remote control. They secured a target to make sure the composite picture lined up with my real brain.

They moved the magnet one more time, a few centimetres forward from the motor cortex, and, according to the map, they found the primary target. They fired away.

It felt a bit like something was buzzing and clicking in the front of my head, but was otherwise easy and comfortable.

I repeated this process twice a day for 15 days, following a few days of testing to make sure there were no negative side effects. There’s no standard protocol for someone with my bizarre basket of symptoms.

But there were a few effects that I noticed — as if for the first time — following months (years?) of DLPFC dormancy. My sensitivity to light increased so much that I could hardly be exposed to it for any length of time without blindfolding myself. When I did, it would reduce my somatosensory symptoms, especially tingling and numbness in my limbs. This sounds absurd, but I later discovered, in this scientific article, that it commonly plagues people with “visual snow” symptoms: “migratory paresthesia.” While I (hypothetically) gained energy and initiative, I also suddenly had more visual problems. I’ve been wearing blue-blocking glasses ever since, and sometimes I still blindfold myself to feel my limbs again.

This seems to indicate some kind of hyperactivity in my visual cortex and, after talking with another doctor, perhaps a deficit of acetylcholine. Acetylcholine transmits nerve impulses within the central and peripheral nervous systems, and can either stimulate or block responses.

“Dear lord,” I thought. Two steps forward, in this case, and one step back.

I filed that question for another day.

Measuring changes in brainwave activity

When I was talking to the doctor, I shared some research about how folks with a similar symptom profile have abnormal delta wave expressions, particularly in the visual cortex. After all, I had already (of course!) been researching what could possibly explain all the visual distortions. There was nobody who would do that for me.

I asked whether there was any way to get a measurement of the wave patterns in my brain. The dozen or so doctors I’d already seen in Winnipeg were unable to find a way to measure the brain’s activity. Again, frustrating, but it’s what I’d come to expect from government medicine.

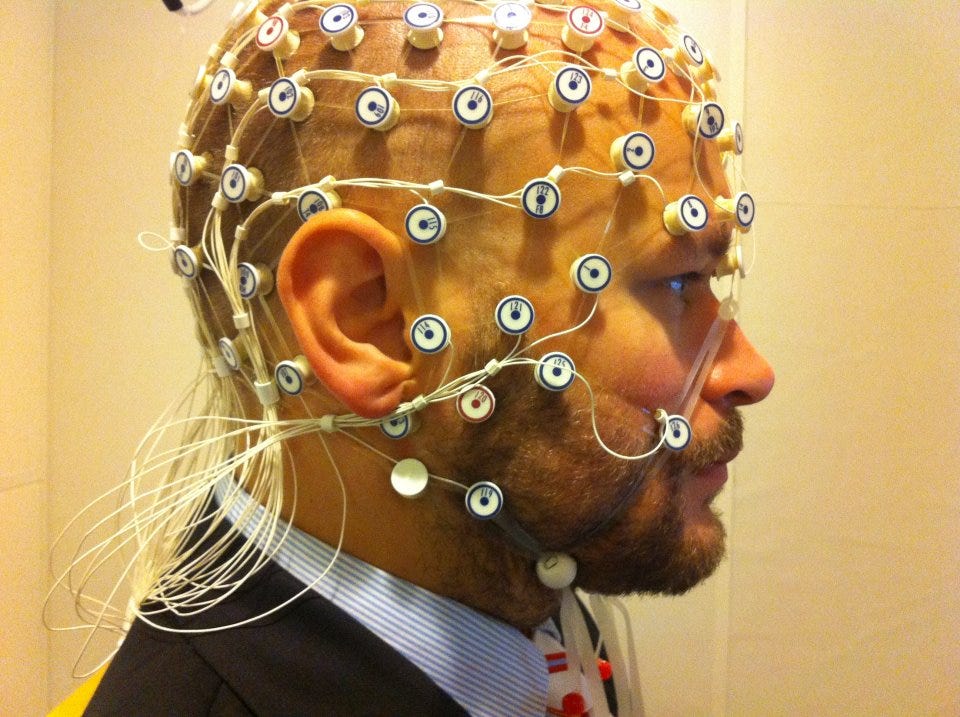

The following day, she called and told me that she knows of a university researcher who would do a measurement out of the kindness of his heart. I jumped at the opportunity and had an EEG done at the beginning, middle, and end of the treatment. I don’t have the results yet, but perhaps it will reveal something interesting when they come through.

A foot in the door, with more hills to climb

rTMS was not a panacea, and it was not a cure. But it feels like a foot in the door, which might give me enough focus to “level up.” It was so effective at doing what it was supposed to do, that I started to wonder what other brain stimulation techniques might have in store for me.

When I finished Dr. Elliot’s book, I moved on to Dr. Norman Doidge’s book, The Brain’s Way of Healing, and after learning about a few more novel approaches, I procured a couple of devices: a tDCS machine (transcranial direct current stimulation), which is like an electrical jump-start device for your brain; a Vielight machine, which fires infrared light at the default mode network; and I’m on the waiting list to receive a PoNS device, too. The PoNS device, an acronym that stands for Portable Neuro Stimulation device, enhances neuroplasticity by stimulating the tongue, which sends signals to the brainstem. It’s been particularly helpful for folks with Parkinson’s or MS, diseases which also express altered somatosensory processing.

I can’t afford to buy these things, and yet I can’t afford not to. I’ll compare and contrast their functions, but first, I’ll describe my visit to the Mind-Eye Institute in Chicago.