Medication can be a double-edged sword—while it has the potential to further destabilize a nervous system that’s already been injured, in the right dose, it can also act as a miracle molecule that restores balance and supports healing. On this N=1 journey of recovery and exploration, I've been experimenting more and more with low doses of complex molecules. I’ve spent a lot of time using herbs, but I believe I’ve reached a limit on what they’re able to accomplish alone. I’m seeking to understand whether it's possible to further nudge body systems that were kicked out of alignment.

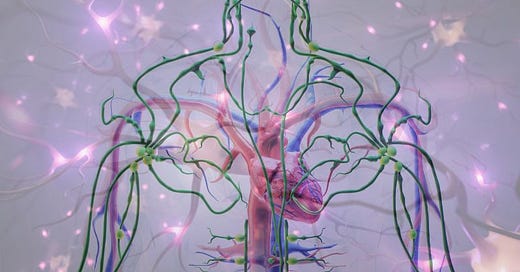

The interconnected web of brain, gut, hormone, and cardiovascular systems all play crucial roles in recovery from brain injuries of all kinds, whether concussive or medication-induced (“iatrogenic”). Beyond that, these systems require a level of understanding that most of us never anticipated needing to develop. Yet here we are.

The Hidden Complexity of Nervous System Disruption

The withdrawal that initially caused such severe disruption to my system is more common than generally acknowledged in medical literature. What's particularly fascinating—and troubling—is how this phenomenon extends beyond just sleeping medications or the ever-ubiquitous antidepressant. Similar patterns of nervous system destabilization happen when the body is impacted by various medications that interact with the nervous system. Increasingly, this also applies to popular psychedelics, including psilocybin and LSD, which are being used more and more, ironically, to help recover nervous system function.

The common thread? Structural changes to neurotransmitters and neurons that fundamentally alter how our nervous systems function throughout the whole body.

I’ve been particularly captivated by a theoretical synthesis by Adele Framer, who has supported thousands on a forum dedicated to helping people recover. She also participated in a comprehensive study of accounts by these individuals.

Understanding the Two-Phase Journey

The path through medication-induced nervous system changes typically unfolds in two distinct phases. The theory is as follows:

The Acute Phase: The Initial Storm

This is where we first realize something isn't right. The acute phase brings those infamous "brain zaps," waves of nausea, light sensitivity, tinnitus, and out-of-character emotional tsunamis that are all too often dismissed as "just anxiety,” or some other pathology. In reality, these symptoms represent the initial shock to a system suddenly forced to function differently.

The Autonomic Instability Phase: When Everything Locks In

This longer-term phase is where things get particularly interesting—and challenging. The body develops an exquisite sensitivity not just to medications, but often to supplements, foods, and environmental stimuli. It's as if the volume knob on your nervous system has been turned up to maximum, with the alerting system sending constant, intense signals to the adrenal glands, triggering floods of stress hormones.

At the heart of many medication-induced nervous system changes lies a complex process that often begins with serotonin receptor adaptation. When medications like antidepressants or psychedelics alter serotonin levels, the brain responds by downregulating serotonin—essentially reducing their numbers to protect against overstimulation. This is the brain's natural protective mechanism, but it can have far-reaching consequences.

The downregulation process is particularly significant because:

It affects multiple receptor subtypes throughout the brain and body, including other neurotransmitter systems beyond serotonin

The changes can persist long after medication discontinuation and is experienced as neurological pain

Recovery requires not just receptor repopulation but also the restoration of normal signalling patterns—which is much harder to accomplish and likely won’t happen without targeted work

In sum, when medications are used and then stopped, these downregulated receptors struggle to maintain normal signalling patterns. Think of it like a radio trying to receive signals with fewer antennas—the message might still come through, but it's likely to be distorted or incomplete. This disruption extends beyond affects sleep, mood, digestion, temperature regulation, heart rate, limb sensation, and other fundamental bodily processes.

Uniquely Individual Responses

One of the most perplexing aspects of this journey is its variability. While some people seem to bounce back quickly from medication changes, others face months or years of challenges. Why?

Researchers have proposed two fascinating theories to explain this difference:

The Slow Receptor Repopulation Theory:

Some individuals simply take longer to regenerate and repopulate their receptors, leading to extended periods of dysregulation and overwhelming changes to neurons and firing patterns.

Rapid Neuroplasticity:

Ironically, having a more adaptable brain might make repair harder. The theory suggests that highly neuroplastic brains adapt more thoroughly to medications, requiring more time and effort to readjust when those medications are removed (ie. until something initiates plasticity again).

This variability doesn't indicate any inherent flaw—it simply reflects the incredible complexity of our nervous systems and their individual adaptation patterns.

When Fight-or-Flight Gets Stuck

Even after receptors begin to repopulate or re-regulate, many people continue to experience symptoms. This persistence points to a broader disruption of the autonomic nervous system, particularly in the locus coeruleus—our brain's primary arousal centre. When this system becomes disinhibited, it creates a self-perpetuating cycle of hyperarousal that can feel impossible to break.

This likely explains why traditional interventions often backfire. Stimulating substances like bupropion, mirtazapine, or even natural alternatives like rhodiola can worsen symptoms by further activating an already oversensitized system. Even medications meant to calm the system can provoke paradoxical reactions, as the hyperactive alerting system fights against being suppressed.

The journey through nervous system destabilization also reveals troubling gaps in our healthcare system. While modern medicine has made remarkable advances, it frequently functions as a blunt instrument when precision tools are needed. This becomes particularly evident in cases of medication-induced injury.

Standard medical diagnostics often fall short in capturing the complex nature of nervous system disruption. Functional testing, while valuable, remains underutilized and often inaccessible. Those of us who have battled through the healthcare system have learned—likely the hard way—to become intimate observers of our own body cues and reactions. This hard-won knowledge becomes crucial in adapting treatment approaches and doses.

Troublingly, medication-induced injury is frequently misdiagnosed. The emergence of anxiety, panic, and irritability is often mistakenly interpreted as the onset of new psychiatric conditions. This leads to what Robert Whitaker describes in "Anatomy of an Epidemic" as a vicious cycle: symptoms are treated with additional medications, whose side effects then compound the original problems, potentially leading to lifelong medication dependence for multiple compromised body systems.

One Possibility for Balance: Lamotrigine

In this complex landscape of neural recovery, lamotrigine (Lamictal) has emerged as an intriguing tool for some individuals. Unlike medications that forcefully push the nervous system in one direction or another, lamotrigine appears to work by helping restore natural balance by increasing GABA (a calming neurotransmitter) and reducing glutamate (an excitatory neurotransmitter).

However, the key lies in approach, dosing, and duration of use. The standard psychiatric starting doses are often far too high for sensitized systems. Instead, success often comes through what might seem like impossibly low doses—sometimes as little as 0.5mg daily. Finding your "sweet spot" requires patience and careful attention to your body's signals.

If considering lamotrigine, keep in mind:

Start with microdoses if you're sensitive (which requires a special prescription or careful pill cutting)

Watch for signs of improved sleep as a positive indicator (normalized sleep = right dose)

Be prepared for a 6-12 month journey of careful titration (requiring experimentation)

While the pharmaceutical industry generally pushes newer, more expensive medications, there's often overlooked value in older medications with decades of research and clinical use behind them. These medications can sometimes be thoughtfully repurposed for recovery and long-term support, often at doses far lower than typically prescribed.

Medications are typically thought to have singular applications, but many have multiple "off-label" uses that can be explored for healing or support. This is particularly relevant when dealing with complex nervous system issues that don't fit neatly into standard diagnostic categories.

Creating Conditions for Healing

It's crucial to remember that while our nervous systems may be temporarily disrupted, they're not inherently damaged. What we're dealing with is iatrogenic neurological dysregulation—a disruption in the body's feedback mechanisms that maintain homeostasis. The good news? Our nervous systems have remarkable capacity for repair through neuroplasticity, provided we create the right conditions: stress reduction, sleep quality, nutrition, movement, social support, and indeed, the right natural and pharmaceutical compounds to restore signalling errors.

For those who have endured lengthy battles with the healthcare system, personal experience with diagnostics and body cues becomes invaluable. While this shouldn't replace professional medical guidance, it often helps in recognizing early warning signs, identifying interventions, and determining appropriate dosing.

The journey through medication-induced nervous system changes requires us to think beyond the problematic "chemical imbalance" model that has dominated psychiatry for so long. Instead, we need to embrace a more nuanced understanding of neuroplasticity and system regulation.

This experience is real. The symptoms aren't imagined or due to some intrinsic defect or pathology, and recovery is possible. While tools like lamotrigine may help, the key lies in understanding your unique nervous system and creating conditions that support its natural healing capacity. It's slow, gruelling, necessary work.